library(tidyverse)

cinnyris <- read_csv("https://raw.github.com/jacobccooper/biol305_unk/main/datasets/cinnyris.csv")

male_cinnyris <- cinnyris |>

mutate(Genus = as.factor(Genus)) |>

mutate(Species = as.factor(Species)) |>

mutate(Subspecies = as.factor(Subspecies)) |>

filter(Age == "Adult") |>

filter(Sex == "Male") |>

select(-`Collection Name`, -Locality, -Country, -Age,

-`Notes / Existing Damage Precluding Measurements`) |>

na.omit()15 Multivariate methods

15.1 Multivariate analyses

Multivariate analyses are commonly used to help understand the variation that exists in large, multidimensional datasets. These analyses can help us understand relationships among individuals and help us determine how many groups (and what groups) exist in a dataset.

For this particular walkthrough, we will be using data on the Northern Double-collared Sunbird Cinnyris reichenowi sensu lato complex from equatorial Afromontane regions (Cooper et al. 2021a, b).

15.2 Principal components

Click here for an overview of PCA

A very common method of visualizing variation in population is using principal components analyses (PCA). Principal components help collapse multidimensional data into a few dimensions that explain the most variation possible across the dataset.

For principal components, we want to use the library vegan.

library(vegan)Loading required package: permuteThe function for principal components in vegan is rda, which will only work on a whole dataframe with no non-numeric data. Thus, we must create a new object of only numerical data and then re-merge it with the original dataframe. The row order is maintained, so this will not be an issue.

male.cinnyris.data <- male_cinnyris |>

select(-Genus, -Species, -Subspecies,

-Collection, -Catalog, -Locality2, -Sex)

cinnyris.pca <- rda(male.cinnyris.data)

cinnyris.pca

Call: rda(X = male.cinnyris.data)

Inertia Rank

Total 23

Unconstrained 23 6

Inertia is variance

Eigenvalues for unconstrained axes:

PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6

15.620 4.443 1.940 0.877 0.076 0.040 Above, we can see that we now have a complex object that contains our PCA. We can use the function biplot to see how our data look and how our variables contributed to the principal components.

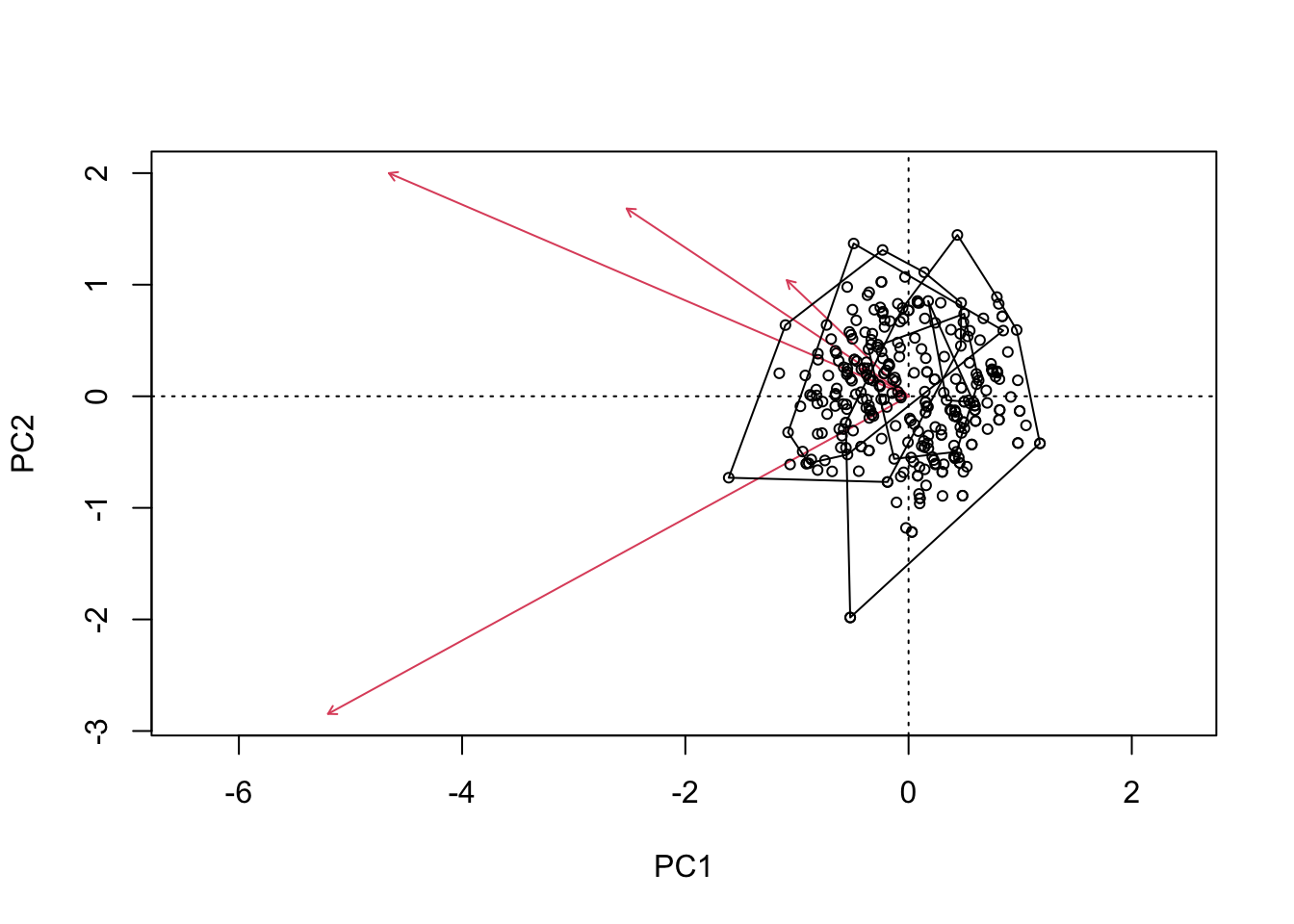

biplot(cinnyris.pca)

ordihull(cinnyris.pca,

group = male_cinnyris$Subspecies)

We can also do a ggplot to color our data and see how it works. Let’s combine our datasets so we can do this.

cinnyris.male.pca <- cbind(male_cinnyris,

# extract PC values

cinnyris.pca$CA$u)

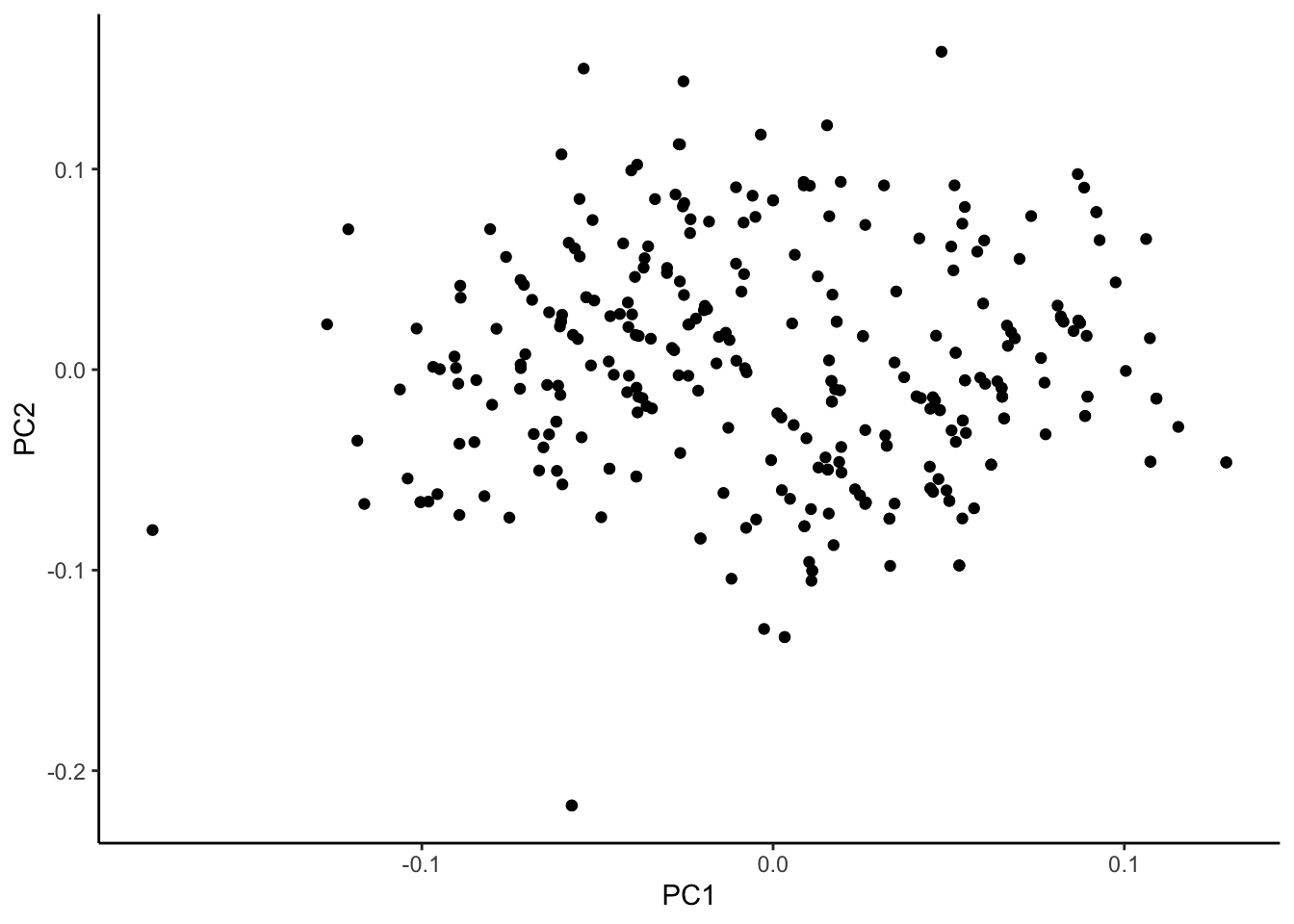

ggplot(cinnyris.male.pca, aes(x = PC1, y = PC2)) +

geom_point() +

theme_classic()

To the naked eye, these data seem to fall into two major clusters. This can be examined again, this time assigning colors to one of our explanatory variables: subspecies.

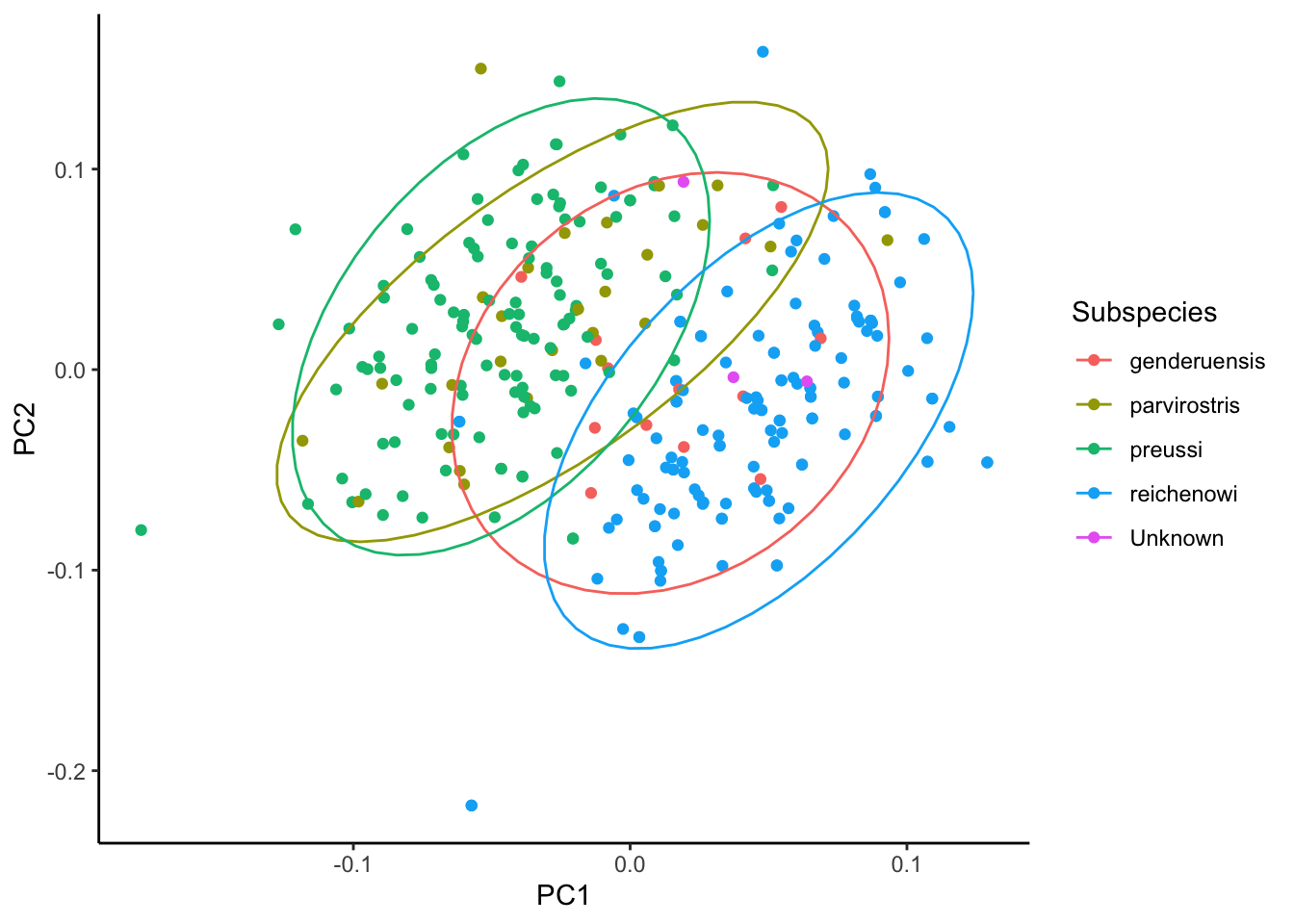

ggplot(cinnyris.male.pca, aes(x = PC1, y = PC2, colour = Subspecies)) +

geom_point() +

stat_ellipse() +

theme_classic()Too few points to calculate an ellipseWarning: Removed 1 row containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_path()`).

As we can see, many of these birds fall into one of the two groups. Only one population - genderuensis - seems to really bridge both groups.

The following shows how each variable contributed to each principal component:

cinnyris.pca$CA$v PC1 PC2 PC3

Right.wing.chord -0.61936877 0.498711666 0.60193981

Tail.length -0.69190828 -0.709947486 -0.12739287

Culmen.length -0.33598591 0.419621089 -0.62835637

Bill.depth..base.of.feathers.on.mandible. -0.01633872 0.004353418 -0.01231269

Bill.width..base.of.feathers.on.maxilla. -0.05865394 0.061714372 -0.09962101

Left.Tarsus -0.14509132 0.259522190 -0.46532983

PC4 PC5

Right.wing.chord 0.07304690 -0.001241684

Tail.length 0.02988534 -0.008716903

Culmen.length -0.53855805 -0.161236784

Bill.depth..base.of.feathers.on.mandible. -0.05951994 0.216257889

Bill.width..base.of.feathers.on.maxilla. -0.08219923 0.962867346

Left.Tarsus 0.83272259 0.006646209

PC6

Right.wing.chord -0.0002699604

Tail.length -0.0062803042

Culmen.length -0.0125622441

Bill.depth..base.of.feathers.on.mandible. 0.9742958451

Bill.width..base.of.feathers.on.maxilla. -0.2212610835

Left.Tarsus 0.0399226008We can also see the percent variance explained by each axis, which is contained within the eigenvectors of the PCA:

cinnyris.pca$CA$eig/sum(cinnyris.pca$CA$eig) PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6

0.679234583 0.193214694 0.084367157 0.038143954 0.003291025 0.001748588 The first principal component explains 68% of the variation, and the second 19% of the variation.

15.3 Clustering

15.3.1 K-means clustering

Click here for K-means clustering

15.3.2 Hierarchical clustering

Click here for hierarchical clustering

15.4 Homework

15.4.1 Disentangling microbiomes

This is an example problem. These data are from (Couper et al. 2019).

# Run this whole chunk to load data

microbiome <- read_csv("https://zenodo.org/records/4940316/files/MicrobialCommunityAssembly_Dryad.csv") |>

t() |>

as.data.frame()New names:

Rows: 36 Columns: 69

── Column specification

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── Delimiter: "," chr

(69): ...1, PW001, PW005, PW012, PW013, PW014, PW015, PW016, PW017, PW01...

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data. ℹ

Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.

• `` -> `...1`colnames.x <- microbiome[1,]

colnames(microbiome) <- colnames.x

microbiome <- microbiome[-1,]